Once upon a time, the internet was described as an “information superhighway”. In truth, it more closely resembles the back alley behind a funfair: noisy, sticky underfoot, and populated by people selling things you probably do not want but will end up buying anyway. It is not defendable in any serious sense, and the extraordinary thing is that everyone knows this but insists on behaving as if surprise breaches and collapses are acts of God rather than consequences of design.

Thomas Dullien (Halvar Flake) called this out in 2017 and the question “Why are we not making a defendable internet?” was revisited in 2022/23.

A “defendable internet” could mean one that is resilient and reliable, a place where data is not routinely stolen, services do not fall over every Tuesday, and personal privacy is not treated as a quaint hobby for paranoiacs. The technologies to build such a thing exist. What is missing is any genuine appetite to use them. The undefendable internet is not the result of ignorance or inability. It is the result of preference.

Historical foundations

The roots of the problem are tangled firmly in the past. The ARPANET of the late 1960s was designed by researchers who assumed anyone plugging into it would be a friendly academic, perhaps with a beard and a fondness for mainframes. Security was not so much an afterthought as a thought no one ever had. The first protocols were built to move data, not to keep it safe from prying eyes or malicious intent.

Then came the 1990s, when the World Wide Web erupted like a particularly excitable volcano. Protocols designed for collegial exchange were suddenly expected to handle banking, power grids, and entire governments. Security measures were hastily bolted on afterwards: SSL, firewalls, intrusion detection. One might as well add armour plating to a papier-mâché tank. The result is that we still rely on creaky protocols like DNS and BGP, patched to within an inch of their lives but fundamentally insecure.

IPv6, introduced in the mid-1990s as the future-proof successor to IPv4, is still in the process of being adopted, in the sense that glaciers are still in the process of moving. The global internet, in short, is balanced on top of infrastructure built in a time when the worst you feared from your network was a crashed printer queue.

Cultural mindset

If history gave us bad foundations, culture gleefully built a tower block on top of them using chewing gum and enthusiasm.

The mantra of the modern technology world has long been “move fast and break things.” A wonderful principle if you are building skateboards; less so if you are running hospitals. Security has always been the boring relative at the party, the one muttering about fire exits and the proper storage of sausages. Developers receive accolades for features, executives for growth, but very few for patching.

Failures, when they occur, are blamed on users. You used password123? You clicked the suspicious link? Clearly

it is your fault that the bank’s entire fraud detection system collapsed. Never mind that systems are designed to

be confusing, inconsistent, and exhausting to navigate. End-users are the designated scapegoats for structural

negligence, because it is cheaper than fixing the actual structures.

Economic and incentive structures

Markets, we are told, reward efficiency. What they actually reward is cheapness and shininess. Security is neither.

For device manufacturers, patching is a cost, not a selling point. Why spend money on updates when your customers can be persuaded to buy a new model instead? For software vendors, “secure by design” is a phrase reserved for marketing copy, not for budget allocations. Compliance frameworks encourage checklists, not defences, so companies hire consultants to produce glossy reports while leaving their servers wide open.

Cyber-insurance has become the equivalent of paying a man in a trench coat to whisper “there, there” after a burglary. The claims are paid, the systems remain vulnerable, and the cycle continues. Meanwhile, the race to the bottom in consumer electronics ensures that insecure devices proliferate by the billion. The market rewards whoever ships first, not whoever ships safest.

At the platform level, security does not sell. Facebook, after all, did not conquer the world by being the safest place to store photographs. It conquered by being the most addictive.

Political and geopolitical dynamics

If you thought states might intervene in the name of public safety, allow me to disabuse you. Governments are not exactly in the business of defending the internet; they are in the business of using it as a battlefield.

Intelligence agencies hoard zero-day vulnerabilities the way dragons hoard gold, because they might come in handy for knocking out an opponent’s infrastructure later. That these same vulnerabilities also leave domestic hospitals, banks, and schools wide open is apparently a regrettable but acceptable side effect.

Meanwhile, the world cannot agree on what sort of internet it even wants. The US favours an open internet (with corporations doing the extracting). China favours a tightly controlled internet (with the state doing the extracting). The European Union favours a regulated internet (with regulators extracting fines). None of these models are particularly interested in building something genuinely safe for the user.

Add to this the lobbying clout of tech giants, and you get political inertia. It is hard to imagine a parliament voting for strict liability laws when the platforms in question fund election campaigns. The undefendable internet persists, in part, because too many powerful actors benefit from its insecurity.

Technical realities

Even if everyone suddenly agreed to fix the internet, the task would be akin to repairing an aircraft mid-flight, with the added complication that the aircraft is made of random spare parts and is on fire.

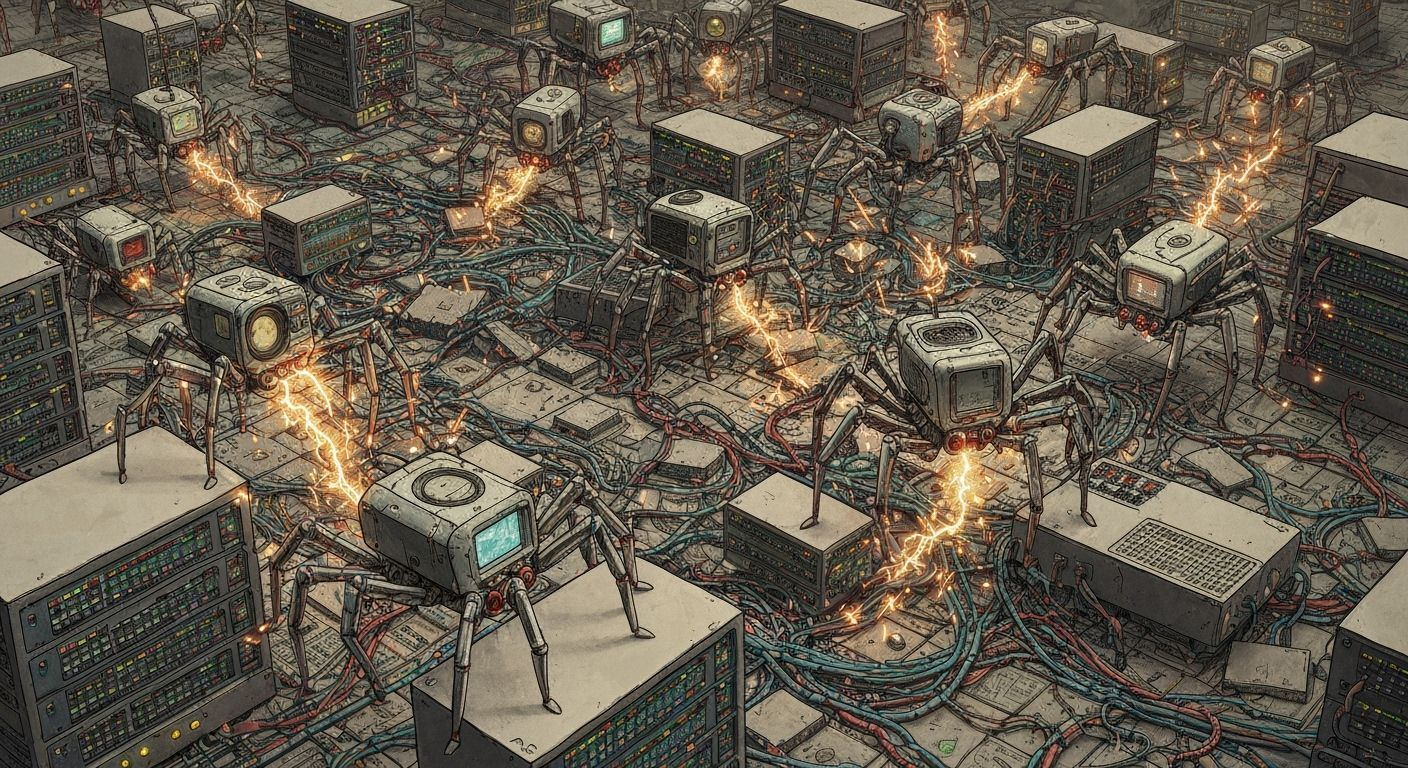

The internet’s technical stack is a nest of interdependencies. Modern applications rely on thousands of open-source libraries, many maintained by a single volunteer. One of these libraries fails, and half the internet falls over. This is not speculation; it happens regularly.

The protocols themselves are fragile. DNS can be poisoned, BGP can be hijacked, and email is practically begging to be abused. Security add-ons like DNSSEC exist, but their adoption is slow, uneven, and forever optional. The system remains reactive: patch after compromise, bandage after haemorrhage.

And then there is the Internet of Things, which has become the Internet of Unpatchable Junk (IoUJ). Billions of cameras, fridges, and doorbells ship with permanent vulnerabilities. Many of them will still be humming away in 2040, diligently waiting to be conscripted into the next botnet.

Legal and regulatory environment

One might expect the law to step in. Instead, it has staged an elaborate pantomime.

Europe has produced sweeping regulations like the GDPR and the Digital Services Act. These have teeth, but they mostly bite the ankles of smaller organisations. Large platforms simply treat fines as an operating expense. In the US, liability for insecure software remains almost non-existent. If a company sells you an operating system riddled with flaws, your only real recourse is to wait politely for a patch and pray it arrives before the ransomware does.

Cross-border enforcement is laughable. Cybercriminals do not respect jurisdictional boundaries, and by the time international law enforcement convenes its task forces, the attackers have already moved on. In practice, many states act as safe havens for cybercrime, as long as the victims live somewhere else.

And so compliance theatre reigns. Organisations produce binders full of policies and declare themselves compliant, even as their systems crumble in practice. The law provides paperwork, not protection.

Psychological and human factors

Finally, there is the problem of people, who are frankly ill-suited to running complex global networks.

Ordinary users suffer from security fatigue. They are asked to memorise dozens of unique passwords, interpret cryptic warnings, and navigate endless pop-ups about cookies and consent. Inevitably, they give up and click “yes” to everything. It is not stupidity; it is survival.

Organisations suffer from optimism bias. Executives assume breaches will happen to someone else, and when they do happen, they treat them as public relations problems rather than structural failures. As long as the damage can be spun or insured away, there is little incentive to change.

In short, human psychology colludes with systemic neglect to make the undefendable internet seem normal. People accept insecurity because the alternative looks exhausting, expensive, or politically impossible.

Ethical questions

Do we even want a defendable internet? That is the question nobody likes to ask out loud.

Surveillance capitalism depends on insecurity. Authoritarian control depends on insecurity. The global digital divide depends on insecurity. Many of the most powerful players in this game would lose their advantages if the internet suddenly became safe, private, and genuinely resilient.

A truly defendable internet might mean trade-offs: fewer conveniences, fewer profits, fewer opportunities for surveillance. It would also mean higher costs and slower roll-outs. So far, almost nobody has been willing to pay that price.

Emerging risks and trends

As if this were not bad enough, new challenges keep lining up at the door.

Billions of insecure IoT devices are already out there, and they are not going anywhere. Quantum computing threatens to make today’s cryptography obsolete in the not-so-distant future. Artificial intelligence gives attackers new tools for probing, phishing, and overwhelming systems faster than defenders can react. AI amplifies. And the world is busy fragmenting into competing internets, each more interested in control than in resilience.

Possible futures

The road ahead seems to look somewhat like:

- More of the same: Breaches, botnets, ransomware, periodic outrage, no systemic change.

- Collapse: A catastrophic incident (not necessarily digital) is either the end or it forces hasty reform, probably at the expense of civil liberties.

- Reform: Liability, secure-by-design mandates, genuine funding for digital infrastructure, theoretically possible, practically highly unlikely.

- Balkanisation: Regional internets emerge, some secure, most repressive, none particularly user-friendly.

Conclusion

The undefendable internet is not a tragic accident. It is a deliberate consequence of choices made over decades: choices that prioritised speed over safety, profit over resilience, control over freedom, and convenience over responsibility.

To build a defendable internet would require more than protocols and patches. It would demand cultural change, political courage, economic restructuring, and perhaps most difficult of all, human patience.

At present, such things appear scarcer than IPv6 adoption. And so we stumble forward on a machine cobbled together with duct tape and denial, telling ourselves that it is progress, while privately hoping that the next catastrophic collapse will happen on someone else’s watch.