When we imagine evolution, we often picture it unfolding at a leisurely, predictable pace, small changes stacking up over time like bricks in a wall. That’s the traditional view: gradualism, the slow grind of nature perfecting its handiwork. But what if evolution doesn’t always play by those rules? What if nature has a taste for the dramatic, long stretches of calm, interrupted by bursts of sudden change?

That’s the idea behind punctuated equilibrium (PE), a theory introduced in the 1970s by palaeontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge. Rather than a smooth evolutionary curve, PE proposes a jagged rhythm: long periods where species remain largely unchanged, punctuated by short, intense episodes of change, often triggered by environmental disruption or internal developmental shifts.

Evolution’s stutter: bursts and pauses

According to PE, most species spend the majority of their existence in stasis, genetically stable, morphologically consistent. Then, at certain critical moments, new forms arise rapidly, either replacing older species or branching off into something entirely novel. Crucially, these changes aren’t necessarily driven by slow adaptation to the environment. Instead, they may be set off by deep internal mechanisms, developmental thresholds, genetic bottlenecks, or a change in the rules during embryonic growth.

The fossil record supports this view. Rather than neat transitions from one form to another, what we often see are abrupt appearances and disappearances. Species emerge, linger in relatively stable form for thousands or millions of years, then vanish or morph with surprising speed. PE doesn’t see these patterns as gaps or accidents, it sees them as the real shape of evolution.

The sphenoid bone: a quiet revolutionary

One of the most compelling biological examples of this principle in action may lie buried at the base of our skull. Meet the sphenoid bone: a butterfly-shaped piece of anatomy that few people outside of medicine or palaeoanthropology ever think about. But according to French researcher Anne Dambricourt-Malassé, this humble bone may have helped propel major leaps in human evolution.

In early foetal development, the sphenoid begins as two separate parts. Around weeks 8–12 of gestation, it undergoes a subtle but critical angular shift, called basicranial flexion. This isn’t just a bit of cranial origami. That single flexion alters the shape of the skull base, repositions the spinal connection (the foramen magnum), and creates space for the brain, particularly the frontal lobes, to expand. It also flattens the face, shortens the jaw, and even contributes to the development of the chin.

Here’s where PE comes into play. This single developmental adjustment, likely triggered by a threshold effect in gene regulation or embryonic dynamics, has wide-ranging consequences, exactly the sort of sudden, systemic change PE describes. It doesn’t require hundreds of generations of selection. It’s a leap, made possible by the internal logic of development itself.

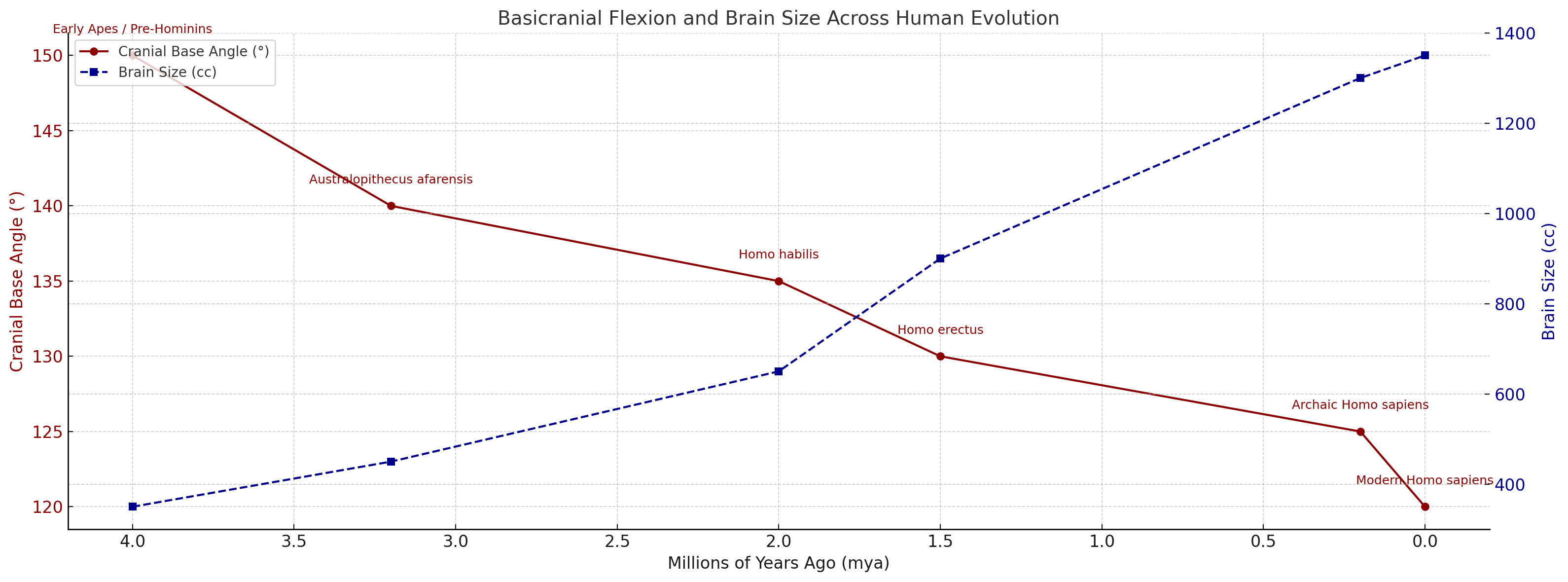

The fossil record reflects this. Over time, we see an increasing degree of basicranial flexion in hominins, Australopithecus with a cranial base angle of about 140°, Homo erectus at 130°, and modern humans down to 120°. Each step is linked to major anatomical and behavioural shifts: larger brains, upright posture, smaller faces. And all of it may hinge on how early in gestation the sphenoid bends. It’s a masterclass in punctuated change, quietly orchestrated from within the embryo.

Shaking the foundations: why PE matters

Punctuated equilibrium doesn’t just shake up palaeontology. It forces a broader reconsideration of how evolutionary change actually unfolds. For one, it makes sense of why transitional fossils are so rare. If most change happens in small, isolated populations over geologically short periods, there may not be many fossils to find.

It also broadens the scope of evolutionary dynamics. PE supports a hierarchical model: gradual changes can still occur within species (microevolution), but larger jumps happen at the level of species formation (macroevolution), and some traits may persist or disappear due to how whole lineages fare, not just individuals. It’s a reminder that evolution isn’t just survival of the fittest, it’s also survival of the timely, the marginal, and sometimes, the lucky.

From biology to everything else

PE’s appeal isn’t limited to biology. Its pattern, long inertia, sudden disruption, appears across human systems too. Think of policy reform: years of bureaucratic deadlock, and then one crisis reshapes the landscape overnight. Or technology: landlines held firm for a century, until mobile networks leapfrogged them into obsolescence. Even history seems to move this way, punctuated, not plodding.

PE also challenges our assumptions about how adaptation works. Not all traits arise slowly under environmental pressure. Some emerge from internal reorganisation, from genetic architecture, developmental processes, or even epigenetic triggers. Stasis, in this view, isn’t failure to adapt, it’s resilience, holding steady until the system hits a breaking point.

Philosophically, it’s a humbling idea. PE undercuts the tidy myth of progress and replaces it with contingency. Evolution doesn’t always inch forward. It stalls. It waits. And then, occasionally, it jumps.

Looking ahead

The future of punctuated equilibrium lies in exploring its mechanics. How do developmental systems, like those governing the sphenoid, tip from one state to another? How do external pressures interact with internal constraints? And what role might epigenetics play in triggering sudden shifts, not just across generations but within one?

Researchers are also starting to apply PE principles to other complex systems, from economic collapses to climate tipping points. The model offers a powerful way to understand when and why slow change turns into upheaval.

In the end, punctuated equilibrium reminds us that evolution isn’t always a slow, meandering river. Sometimes, it’s a dam breaking. And sometimes, the first crack appears in a single, silent bend of bone, hidden in the darkness of the womb.

Very interesting reads

- Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered, published online by Cambridge University Press 08 April 2016

- Ilya Tëmkin, Punctuated equilibria and a general theory of biology, published online by Cambridge University Press 24 March 2025