If you have ever tried to set up a Security Incident Response Team (SIRT) function in a small organisation, you will know that it is not about security, incidents, or even teams. It is about humans behaving badly under stress.

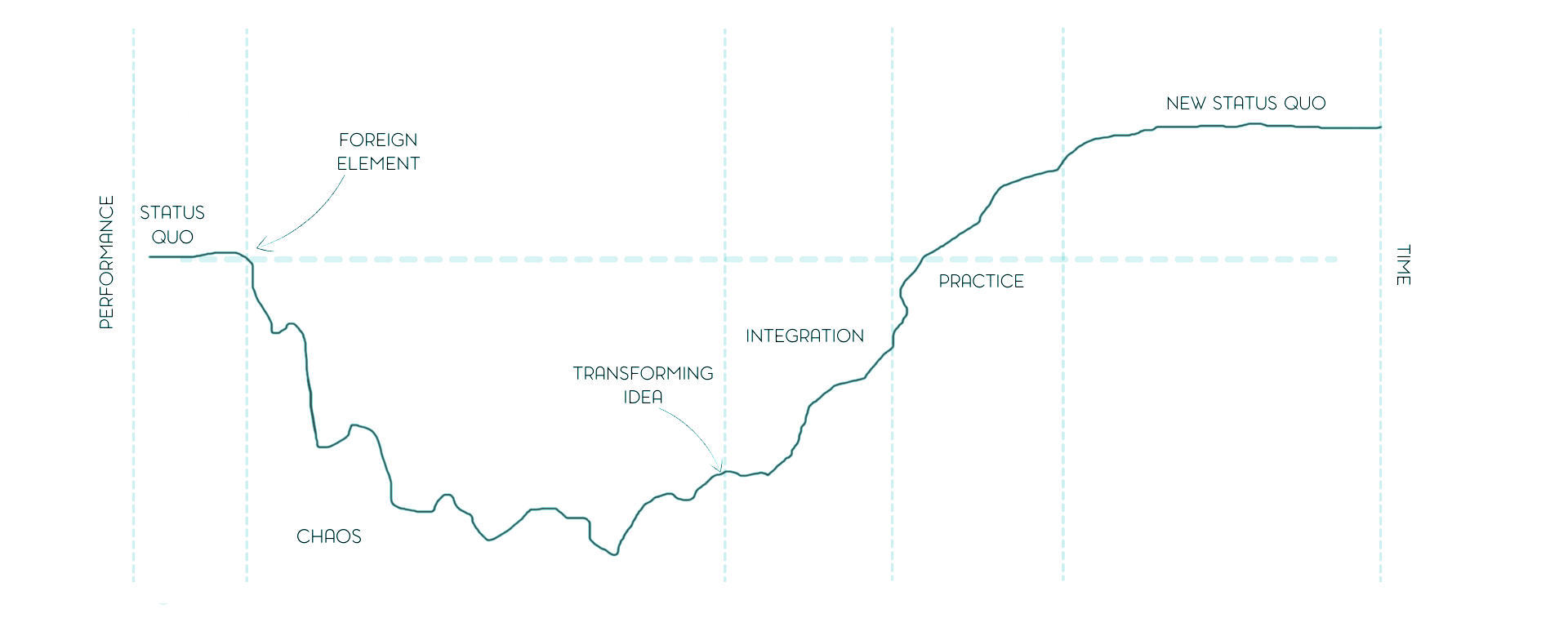

Enter the Satir Change Model, a tool from family therapy that has no right working in cybersecurity, and yet works better than most “cyber resilience frameworks”.

Her five-stage model maps beautifully onto what happens when a small organisation suddenly decides to “get serious about incident response”. Building a SIRT is not about defeating chaos; it is about becoming fluent in it. And once you have done that, “It cannot get any worse” stops being a threat and starts being the team motto making people laugh, sending extra oxygen to their brain.

Stage 1: The late status quo

“We’ve never been hacked, so we must be secure”

Picture a small local organisation. Everyone knows everyone. Passwords are shared like biscuits. The Wi-Fi password is still the founder’s dog’s name. The backup drive has not been plugged in for a year (or more).

No one worries because nothing obviously bad has happened. Yet. This is the late status quo, where stability feels safe but is really just inertia with better branding.

The poor soul asking questions like “who is responsible for data breaches?” receives only blank stares and the sound of coffee being poured.

This is the point in the movie where the audience knows something’s coming. The characters, like people showering in a Hitchcock movie, do not.

Stage 1½: The foreign element

“What do you mean, we’ve been breached?”

Something intrudes. A phishing email that half the staff click on. A ransomware splash screen. Or worse, someone external asking to see your incident response plan.

The “Foreign Element” disrupts the comfortable equilibrium. Suddenly, action is wanted. “Can we have a SIRT by Monday?”

Cue panic meetings. Someone mentions ISO 27001 because it sounds responsible. Someone else says “surely IT can handle it”. You suspect that IT is the problem.

This is where the Satir model earns its keep. It tells you: do not fight the discomfort. The foreign element is not your enemy; it is the only reason anyone will ever change anything.

Stage 2: Chaos

“Everyone panic in an orderly fashion!”

Now you are properly in it. Everyone’s calendar fills with “urgent” meetings titled “Cyber Thing”. Nobody knows who’s in charge. Someone suggests buying a SIEM because it “sounds proactive”. Another proposes unplugging the server “just to be safe”.

This, Satir would say, is “Chaos”. It feels like failure, but it is actually the first moment of learning. The old ways no longer work, and the new ways do not yet exist.

Your role now appears to be part facilitator, part therapist, part sheepdog. You listen to people’s fears, name them out loud, and introduce the radical concept of breathing.

When someone asks, “Can it get any worse?” you smile and say, “It absolutely can, but not for long.” Then you give them biscuits. Chaos is survivable if there are biscuits.

Stage 2½: The transforming idea

Chaos has been raging for days. Every meeting begins with “quick update” and ends with despair. Someone’s suggested buying another firewall, someone else has suggested prayer, and the intern has helpfully printed a list of possible entry points hackers might use.

The list, in all its painful honesty, can include one (or more) of these:

- “Admin” passwords that have not changed since 2017.

- Shared Dropbox folders labelled “Confidential”.

- Publicly exposed test servers from a developer who left three years ago.

- Email filters set to forward invoices to an external Gmail “for convenience”.

- The CEO’s laptop, which connects automatically to any Wi-Fi that says “hotel”.

Everyone stares at the list. It is silent for the first time all week.

Then someone says, quietly: “So… maybe it’s not just about stopping hackers. Maybe it’s about us changing how we work.” Someone else adds “We also need to work on how we respond when things go wrong.”

And there they are, the “Transforming Ideas”.

The moment the organisation realises the threat is not out there, that it is inside, baked into the habits and shortcuts that once made things feel efficient and fast. That insight changes everything. Fear turns into focus. The incident stops being something happening to us, and becomes something we can learn from.

You can almost feel the collective exhale. That’s the magic of the transforming idea, going from panic to possibility.

Stage 3: Integration

“So, we need a plan, then?”

Slowly, the chaos starts to make sense. They work on the list and someone drafts an incident response flowchart. You test it with an adopted and adapted tabletop exercise involving imaginary ransomware and very real biscuits.

(Double) roles emerge:

- An Incident Lead who knows shouting “Fix it!” is not a strategy.

- A Communications Person using honesty early, to beat damage control later.

- A Tech Person who starts documenting.

In facilitation terms, this is “Integration”. The team begins to see themselves as a system that can respond, not just react. Mistakes become stories, not blame sessions.

There is laughter again. Someone designs a SIRT logo involving a flaming bin. Morale improves.

Stage 4: Practice

“Do we really have to run another exercise?”

Understanding a plan is not the same as executing it. New habits take time. And the people who double for SIRT roles now run more tabletop exercises where pretend hackers attack pretend servers and fake phishing emails circulate. Biscuits remain compulsory.

The first few runs are excruciating: roles forgotten, scripts ignored, reply-all disasters. Slowly, through repetition and mild embarrassment, muscle memory begins to form. Response times drop. Scripts shorten. Procedures finally stick.

This is the Practice stage, turning insight into habit. Chaos is still present, but manageable. Laughter becomes a shared coping mechanism rather than panic. The team stops checking the handbook every ten seconds because they know it.

Stage 5: The new status quo

“We are incident response professionals now, apparently”

After practice, the team reaches a new equilibrium.

- Procedures exist.

- Roles are clear.

- The incident log is maintained.

- The SIRT can handle a phishing email without anyone shouting.

The organisation has not become perfect. It is, however, functional and resilient. Fear is replaced by competence (and mild cynicism). Tea and biscuits are mandatory.

This is the new status quo: a small organisation that can respond to incidents because the people running it have learned to handle themselves, not just follow a checklist.

Why the Satir Change Model actually works here

Because most incident response “maturity models” forget that organisations are made of people, not policies.

The Satir model acknowledges that every change starts with disruption, descends into chaos, and only stabilises once people have found new meaning.

It gives permission for things to be messy. It normalises panic as a stage, not a sin. And it replaces the managerial fantasy of “smooth transformation” with the far more realistic “structured improvisation” until we get what works best for us.

If you are facilitating this process, your job is not to make people unafraid, it is to help them notice that fear and cognitive dissonances are just the system learning in real time.

Famous last words

“It cannot get any worse”

A few months later, another incident occurs. This time, everyone knows what to do. No one shouts. The post-incident review happens within 24 hours, and someone even writes it down.

The SIRT handles it so smoothly that management asks if you can “automate it”. You laugh until you cry.

Change, as Satir would say, never stops. The best one can do is meet it with humour, structure, and biscuits.