When we think about evolution, we usually imagine something like survival of the fittest, organisms scrabbling to adapt to harsh environments, with only the strongest traits passing on to the next generation. But what if much of the story wasn’t written in the open battlefields of nature, but quietly, deep inside the womb?

That’s exactly the idea behind the work of paleoanthropologist Anne Dambricourt-Malassé. Her research suggests that one of the most important drivers of human evolution isn’t some dramatic change in diet, climate, or hunting technique, but the early developmental behaviour of a small, oddly shaped bone at the base of the skull: the sphenoid.

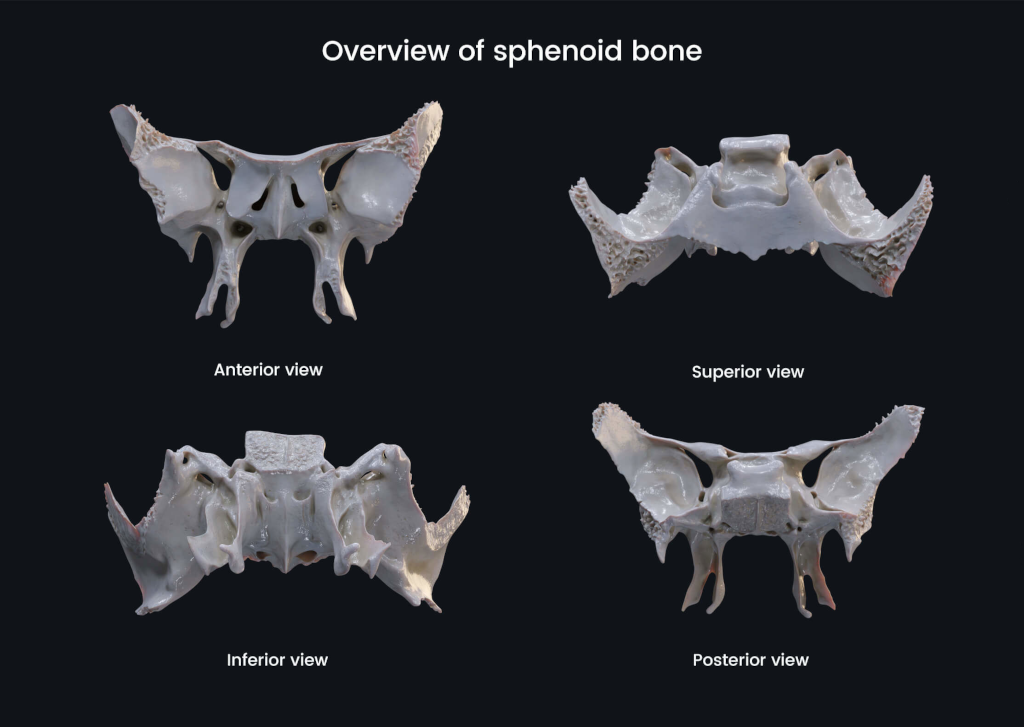

The shape that changed everything

During the first few months of pregnancy, the human skull begins to take shape. In these early stages, the sphenoid bone, an awkward, butterfly-shaped bit of cartilage tucked behind the nose and eyes, starts out in two parts. Then, between weeks eight and twelve, something rather remarkable happens: the two parts begin to bend. This “flexion” is a key moment. It’s not just a bit of embryonic fidgeting. This subtle shift in angle acts like the first domino in a long chain of events, altering the layout of the entire head.

As the sphenoid bone flexes, it changes the angle of the base of the skull. This new configuration makes space for the brain to grow, especially the frontal lobes, the parts responsible for planning, language, and abstract thought. At the same time, it nudges the face into a more vertical position, reduces that classic monkey-like snout, and shifts the hole where the spine connects to the skull (the foramen magnum) forward, setting us up for upright walking.

In other words, this small adjustment deep in the foetus triggers a cascade that reshapes the brain, the face, and the way we move.

From bone to brain to biped

This tiny twist of bone helps explain a whole suite of human traits that seem to appear together in the fossil record. As the sphenoid flexed more over time, we got bigger brains, particularly at the front, while the back of the skull flattened out. Our faces shortened and pulled inwards, giving rise to something you don’t find in other primates: a chin.

Even our upright posture seems to trace back to this same origin. With the foramen magnum moving forward, the spine could align beneath the head, making it much easier to walk on two legs. That in turn encouraged changes in the spine’s curve, the shape of the pelvis, and the way we carry our weight. All these bits evolved together, not because of external environmental shocks, but because of internal developmental processes kicked off early in the womb.

Evolution from the inside out

What makes this model so intriguing is that it offers an alternative to the classic Darwinian story. It’s not saying that natural selection doesn’t matter, of course it does, but it suggests that some evolutionary directions were strongly shaped by internal developmental patterns. Certain changes, like the bending of the sphenoid, opened up new anatomical possibilities. Others were ruled out entirely. Evolution, in this view, isn’t a random walk through genetic space. It’s more like a river carving a path through a landscape of constraints.

Over time, Dambricourt-Malassé argues, this flexion process became more pronounced. In Australopithecus, an early human ancestor, the cranial base angled at around 140 degrees. By the time we get to Homo erectus, it had tightened to 130 degrees. In modern humans, it’s closer to 120. These changes correspond with other major shifts: more complex tools, symbolic thinking, rapid brain expansion. And notably, they don’t require any major new mutations to explain them. Instead, they could be the predictable outcome of how early development unfolds once a certain threshold is crossed.

A quiet revolution in understanding

The mechanics behind this are still being explored. Researchers are looking at how certain genes, particularly HOX genes, which help lay out the basic body plan, guide the development of the sphenoid. There’s also evidence that muscle movements in the foetus can influence how bones ossify (turn to bone), meaning that development responds not just to genes but to subtle biomechanical feedback as well.

Comparing how human foetuses and great apes develop in the womb is also proving valuable. It helps us spot when and how the human path diverged, and whether similar processes are at work in our primate cousins. So far, it looks like the human version of this flexion is both distinctive and unusually influential.

What’s powerful about this model is how it draws together ideas from embryology, anatomy, evolutionary biology, and systems theory. It suggests that some of the big shifts in our evolutionary history, our upright posture, our massive brains, our flat faces, might not be separate adaptations to different problems, but different expressions of the same underlying developmental shift. A shift that started, quietly, deep in the womb, in the way a single bone bends.

Still controversial, but worth keeping an eye on

Not everyone in evolutionary biology is convinced. It’s a departure from the gene-focused models that dominate much of the field. But unlike hand-waving theories about “big leaps” or mysterious missing links, this one makes testable predictions. It can be measured in fossils, modelled on computers, and compared across species. That makes it scientific, and worth keeping an eye on.

If it continues to hold up, the humble sphenoid might just be one of the unsung heroes of our evolutionary story. Not bad for a bone you’ve probably never heard of.

Interesting reads

- Anne DAMBRICOURT MALASSÉ, Évolution du chondrocrâne et de la face des grands anthropoïdes miocènes jusqu’à Homo sapiens, continuités et discontinuités, 2016