The term “woke” began its journey not as a fashionable slogan but as a survival mechanism within Black America. Its trajectory, from literal vigilance to political litmus test, reveals how language can be both weapon and shield.

Survival and vigilance

In its earliest uses, “woke” carried the weight of bodily survival and communal resistance.

In 1923, Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey exhorted his diasporic audience with the cry, “Wake up Ethiopia! Wake up Africa!”, a metaphorical awakening to racial oppression and collective self-determination. You can still look for him in the WhirlWind.

In 1938, blues musician Lead Belly recorded Scottsboro Boys, a song protesting the wrongful conviction of nine Black teenagers in the Jim Crow South. At its conclusion he warned listeners, “Best stay woke, keep their eyes open.” This was not metaphor but instruction: stay alert to danger at every turn. That phrase encapsulated the literal urgency of living under threat of violence from both state and state‑sanctioned actors.

And as early as 1942, workers in the United Mine Workers movement used similar language to describe awareness of wage theft and prejudice: “Waking up is a damn sight harder than going to sleep, but we will stay woke up longer”.

Identity, trauma and consciousness

The term resonates with W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” , the psychological tension of possessing an identity shaped by both self‑worth and constant awareness of racial distortion. Being “woke” came to represent the mental labour of being simultaneously Black and aware of how whiteness viewed Blackness.

That hypervigilance mapped onto daily realities: microaggressions, policing, economic invisibility. Awareness became both defence and burden. By the mid‑1960s, the term had evolved into meaning “well-informed” or “alert to injustice,” a usage recorded in a 1962 New York Times Magazine article titled “If You’re Woke You Dig It", signifying growing public awareness of racial consciousness.

From Black liberation to mainstream culture wars

During the civil rights era and in the Black Power movements that followed, “woke” stood for readiness to resist oppression. “And now that Mr Garvey done woke me up, I am gon’ stay woke”, explicitly linking knowledge to collective action.

Fast-forward to the 2010s and the Black Lives Matter protests following Ferguson and the killing of Michael Brown: “stay woke” changed into a rallying cry in slogans and social media, signalling urgent awareness of systemic racism and police violence.

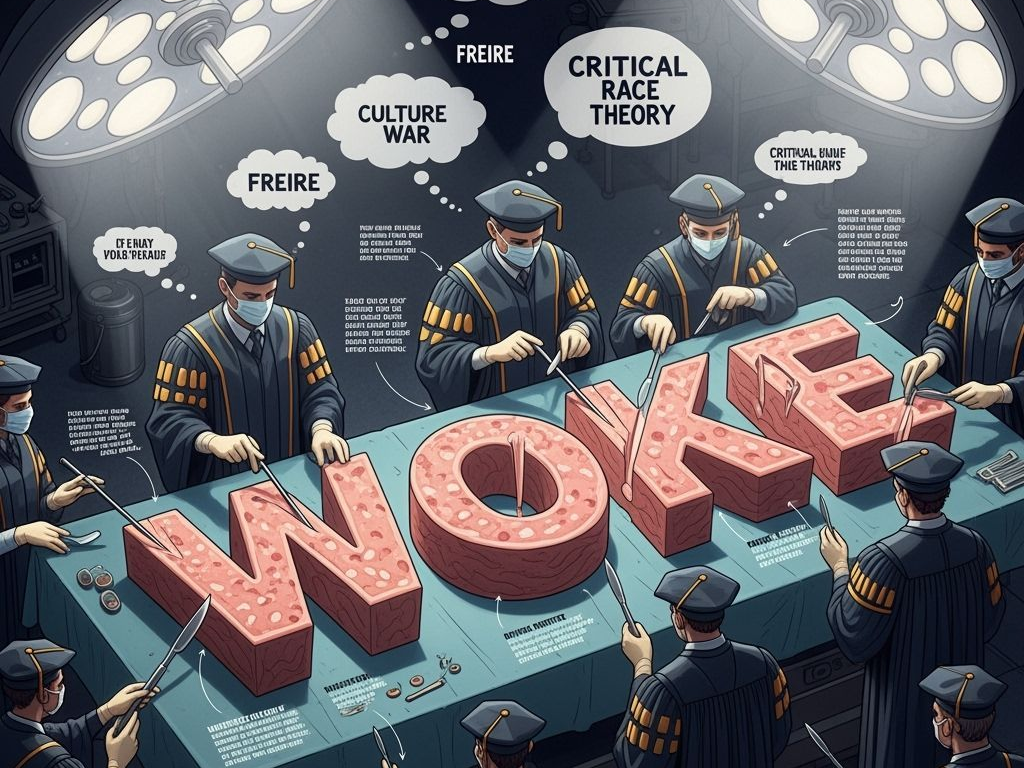

By the 2020s the term had been weaponised by conservatives. Figures such as Florida governor Ron DeSantis turned it into shorthand for liberal ideology and exclusionary identity politics. In so doing, “woke” moved from a marker of political consciousness to a target in culture‑war skirmishes. Right‑wing commentary now routinely treats it as a destabilising force in education, business, and governance.

Philosophical and spiritual dimensions

On one level, “wokeness” echoes the liberatory spirit of consciousness-raising movements. Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968, pdf) promoted awakenings to systemic tyranny, social, political, spiritual. That kind of awareness was not personal vanity but collective insight.

Critics from certain religious or philosophical perspectives draw parallels between woke ideology and ancient Gnosticism: the belief in hidden truth over surface reality. Some argue that woke identity is curated individually rather than grounded in material facts or shared reality.

Intellectual ancestry also traces through the Frankfurt School and post‑structuralists, Horkheimer, Marcuse, Foucault and Derrida, who deconstructed power hierarchies and normalised skepticism of dominant narratives. Woke critics suggest that such philosophical legacies contribute to modern emphasis on identity and language politics.

Why “woke” evokes such fierce reaction

For as much as there is a left vs right, on the left, the word appears to be cherished as a moral code: a recognition of injustice and a commitment to equity. On the right, it seems to be reviled as dogma masquerading as decency. It is characterised by critics as overreach, authoritarian thought control, or simply virtue signalling. Corporations co‑opt the term in marketing campaigns, a phenomenon called “woke capitalism”, leading to further backlash from both activists and conservatives alike.

Within Black communities the term is contested. Some embrace its radical roots; others resent its dilution or distortion by journalists, brands, or political opportunists. Institutions like the NAACP have formally insisted on preserving its historical meaning, warning against cultural appropriation and misuse in legislation such as Florida’s “Stop W.O.K.E. Act”.

A word walked into a culture war …

What began as a code for survival, an instruction to remain alert in a world of racial peril, has become an ideological Rorschach test. “Woke” now carries multiple meanings: it can signify resistance, virtue, performative branding, or the erosion of free speech, depending on who is using it and to what end.

Its power, and its controversy, derive from its adaptability. It reflects society’s evolving anxieties about identity, power and truth, and poses a cruel puzzle: how to honour its radical origins while discerning its present distortions.